Acoustic fingerprinting television

Let's jump to the good stuff: How hard is it to create a program that can acoustic fingerprint a television show? Can we identify the playback position of a video based on audio tracks? For this blog post I'll use The Drew Carey Show, because it's the only show of which I have multiple seasons.

Let’s jump to the good stuff: How hard is it to create a program that can acoustic fingerprint a television show? Can we identify the playback position of a video based on audio tracks? For this blog post I’ll use The Drew Carey Show, because it’s the only show of which I have multiple seasons.

Crash Course

Acoustic fingerprinting is when a condensed audio signal is used to identify a larger audio sample. In practice, this means that given a small clip of audio from a movie or tv show, I would like to be able to identify the playback location where the clip originated. The complication is that, while a clip and it’s origin may sound exactly the same to the human ear, their binary representations may differ to do encoding, compression, or recording artifacts.

When writing about acoustic fingerprinting, it’s implied that the solution implemented needs to scale. What makes this interesting is not being able to match one clip out of dozens of samples, but being able to match one clip out of millions or billions of samples. Efficiency of technique is also implied when writing about fingerprinting. It’s not useful to generate a fingerprint that reduces the possible matches from ten million to a million, but it is useful to reduce the possible matches from ten million to ten. Scale matters, and by-proxy, efficiency matters. While I’ll try to apply scale and efficiency to the techniques in this project, it’s a little out of scope to find and catalogue millions of samples for my tests. For now, a couple seasons of The Drew Carey Show will have to do.

How does Shazam do it?

Shazam does fingerprinting by looking at spectrographic peaks that are “chosen according amplitude, with the justification that the highest amplitude peaks are most likely to survive [sic] distortions…” By listening to a song and finding two spectrographic peaks in the song, the algorithm Shazam uses is able to narrow down the number of potential candidates considerably. This is roughly the method I’ll use: reducing the audio track to a series of spectrographic peaks, tagging the peaks, and associating timestamps with them.

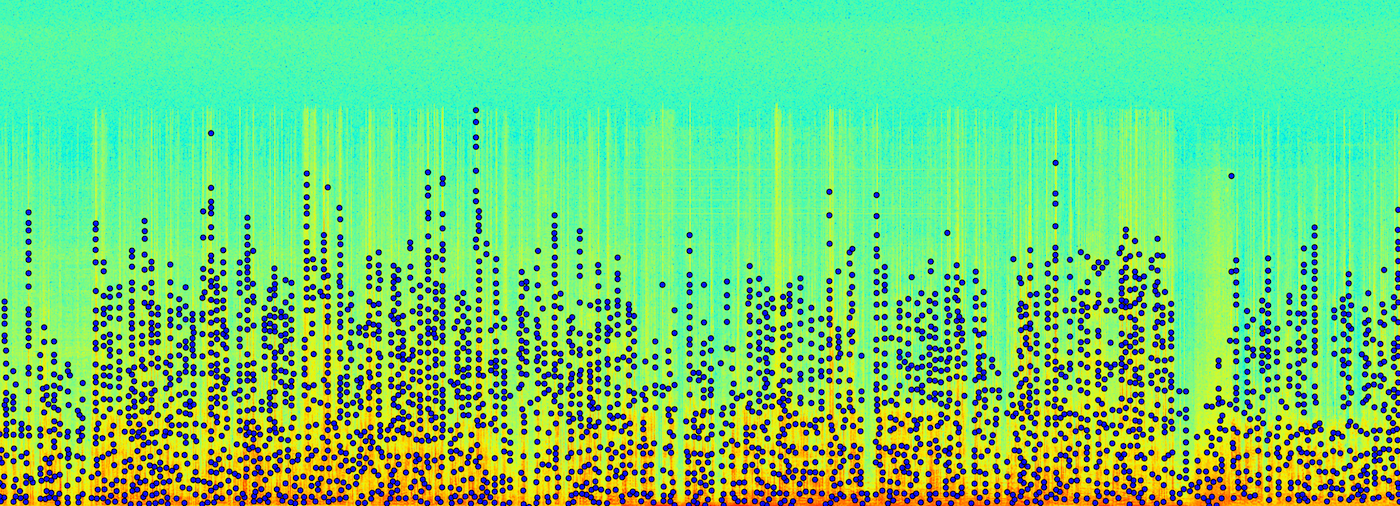

Once we have the audio separated from our video, and in a WAV file, it’s easier to work with. A WAV file is just a serialized bitstream of audio data, usually sampled at 44,100 Hz at 16 bits per sample. To put this into perspective, about a second of two channel audio is about 180Kb. To analyze the data, we can use matlab’s specgram library, which will sample the bitstream at a given window size using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm. FFT is the most common and one of the fastest ways of sampling a signal and breaking it down into its frequency components. So when we feed specgram the bitstream, we get an array of data back that represents the amplitude of frequency ranges of the signal at discrete points in time. Here’s what a WAV file for a couple of minutes of a movie looks like when we break to down by time (x axis), frequency (y axis) and amplitude (chromatic axis where green is low and red is high).

This type of data is really interesting, because when you visualize it like this, you get a sense that this could be basically any signal. Any type of signal that you get in wave format, you should be able to use signal analysis. I’d like to start a company called Sigint, and sell signal analysis tools on a large scale that can help spot patterns in large amounts of singal data.

The graph cuts off at ~2000 Hz, because human beings can’t hear anything higher than that. We can’t hear anything lower than 20 kHz, for that matter. If you look closely you’ll see that there doesn’t seem to be frequencies higher than 1600 Hz on the spectrograph. That’s because, at some point during the encoding process - when the video was being mastered, when it was compressed to DVD, when it was converted to AVI, or when it was converted to WAV - those frequencies were either compressed or eliminated. In the attempt to save disk space, someone decided that the viewer of the movie doesn’t care if there are sounds in the movie above 1600 Hz, and generally they’re right. This reduces the quality of the signal for our algorithm, but if those frequencies don’t exist in popular video formats, then our system will miss them anyway when put to use identifying a clip.

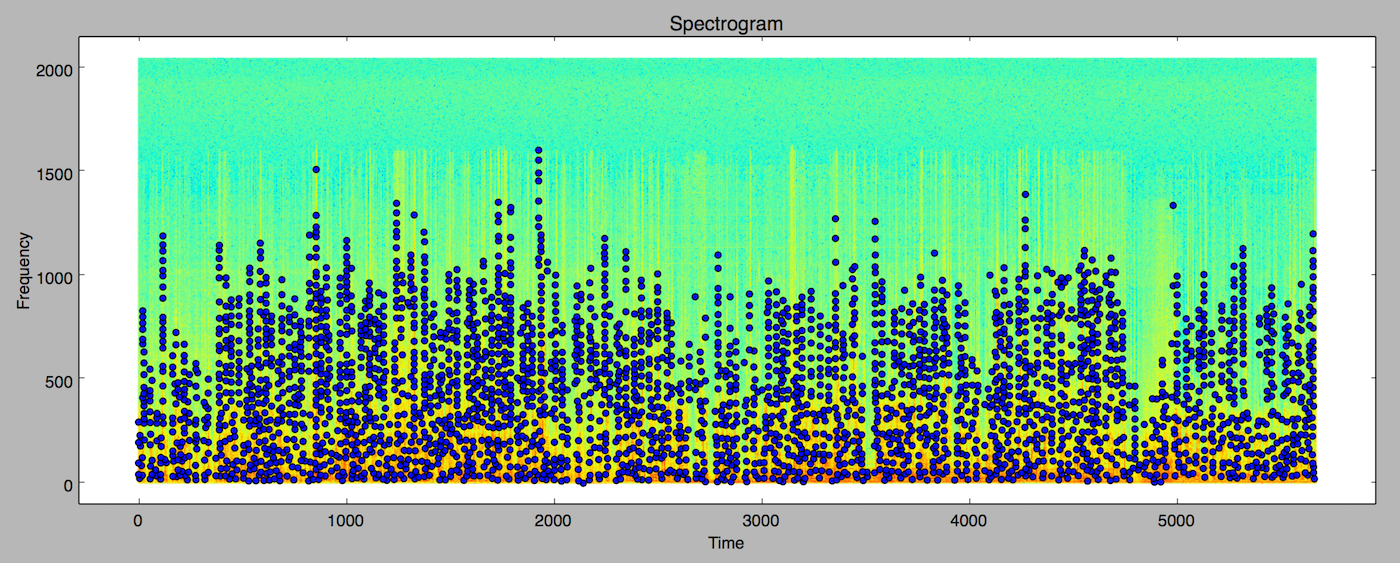

With the data in a format we can reason about, the next part of constructing a fingerprint involves figuring out the unique characteristics in the signal, in this case peaks. What defines a peak? We’ll define it as a given frequency range (R) going above a certain amplitude (A), with no other neighbors being higher for (N) neighbors. If we set R, A, or N too low, we’ll end up with so many peaks that when we use them to build a fingerprint, it will be too broad of an identifier. If we set these variables too high, then we’ll see fewer peaks, resulting in a fingerprint that will require too much capture time to match against. I’ll write about tuning these variables later. Here’s what it looks like when we scatterplot the peaks on top of the frequency data.

Fingerprinting and Indexing

Now that we have a list of peaks for a section of audio, we can uses these peaks to build our episode index. Peaks are just (time, frequency) pairs, e.g. (1197, 1941). Our index could be something like {frequency -> episode}. If we gather the frequency of enough peaks, we should be able to find which collection of frequencies exist sequentially in the same video. The performance of this technique isn’t going to be good though, because it would require multiple operations to lookup the video, and we would have to ensure the order when the query returns. At a minimum you would need to look up two peaks, but you could need many more to ensure that a match exists. What we can do instead is depend on time. If a frequency X is followed by frequency Y in a sample, and are separated by time T, we can use these three characteristics to build a hash, assuming that in any clip X, Y, and T will be roughly the same. For example, if we have two time-frequency pairs, our hash would be:

(941, 2247), (947, 907) murmur3_hash(“907:2247:6”) = 2660468934

When we do a fingerprint lookup by hash, what we want back from the database is the episode and playhead position of that hash. Since two episodes could technically have the same hash and playhead position, we’ll use a compound index on hash, episode, and playhead position. This is pretty basic database stuff, so I won’t go into more detail.

Measuring and Testing

How do we know if this works? We can cut a 10 second clip from an episode and look for a match, which we’ll probably find; we’re running the same algorithm on the a subset of the bitstream we used to generate the fingerprint. The real test for fingerprinting is if the system is good at matching clips that are compressed, distorted, or otherwise altered from the original audio sample. To measure the effectiveness of the system more thoroughly I’ll randomly select 10 second clips from all of the episode we fingerprinted. I’ll then generate several distorted versions of each one:

- Light Background Noise (LBN): Equivalent of a coffee shop.

- Medium Background Noise (MBN): Equivalent of a quiet bar.

- Heavy Background Noise (HBN): Equivalent of a loud bar.

These are crude substitutes for recording actual clips in real watching environment where room acoustics, compression, distortions, and recording artifacts of any kind might disrupt the effectiveness of our algorithm, but they should give us a general sense of how well it would work in a likely application.

To ensure that our system isn’t finding patterns where none exist, I’ll also run these tests for clips from episodes that we did not fingerprint and load into the database. After all, if our system is able to match all of our loaded clips, but misses half of the non-loaded clips, then the system isn’t very good. The classification of outputs will follow positive-negative precision and recall:

- Positive Match: Correctly identified episode.

- False Positive Match: Incorrectly identified episode.

- Negative Match: Correctly identified that there is no match in the database.

- False Negative Match: Incorrectly identified that there is no match in the database.

We will not be matching playhead position, for the sake of simplify the testing process. I’ll assume that if we can match the episode with any confidence, we can simply return the earliest playhead number returned from the database. This is ignoring all the edge cases where episodes have similar sounds like themes, cut music, and phrases, but those seem like problems that can be solved for during implementation of the system, rather than issues we should account for now.

What does “correctly identified” mean? When we run our fingerprinting algorithm on a clip, we’ll get back dozens of fingerprint hashes. If we query the fingerprint database for each hash, we’ll probably find at least one match for some, and more than one match for a few. This type of result lends itself well to using histograms and ranking. If we get back a total of 10 matches, spread over 4 episodes, with the counts 1-1-3-5, my gut tells me the episode with 5-hashes would be correct. Conversely, if we get back 10 matches, spread over 4 episodes, and the counts are 2-2-3-3, I would consider that inconclusive, and therefor a negative match.

An artist’s rendering of histogram-based matching.

This is an “election” so to speak, with plurality marking the winner, but only if the plurality is above a threshold. MATCH_RATIO is yet another variable that we can adjust when testing.

MATCH_RATIO = 0.1 def determine_match(records, match_ratio=MATCH_RATIO): histogram = {} for record in records: if record.episode in histogram: histogram[record.episode] += 1 else: histogram[record.episode] = 1 s = sorted(histogram.iteritems(), key=lambda (k, v): v) match = s[-1] if match[1] > int(MATCH_RATIO*len(records)): return match[0] else: return None

This is a simple algorithm, and that’s why I’m using it. There are cleverer ways of selecting the best match. For instance, if our fingerprinting algorithm is good, and tuned well, the fingerprint hashes from a clip should be present in very few episodes, ideally one episode. We could query for several hashes, returning an episode only if there is a sequential match. E.g for hashes H1 and H2 we get back fingerprints (H1, E1, T2), (H2, E1, T3), (H1, E2, T10), (H2, E2, T1), we would determine that the clip probably matches episode E1, because E2’s hashes didn’t occur in order. In cases where we have more than one possible episode, we could return no match. But there are edge cases to this algorithm that increase the number of variables in an already complex system. The minutiae of a sequential-matching algorithm seem deserving of an entire blog post, not just a brief section in this one.

Test Data

To generate the wav files, I used ffmpeg. To generate the clips, I used my own python script that cuts random selections of each wav file. To generate the distorted versions I used ffmpeg again. You can checkout the repository for more information. Finally, to load and fingerprint two seasons I used my own load script. Before we analyze anything here’s what our data looks like.

data/ the_drew_carey_show/ s01s02_wav/ s01e01.wav … s03s04_wav/ s03e01.wav … samples/ positive/ s01e01.163.normal.wav s01e01.163.LBN.wav s01e01.163.MBN.wav s01e01.163.HBN.wav s01e01.163.SML.wav … negative/ …

The Results

Run Number 1

- PEAK NEIGHBOR COUNT: 20 This is the number of frequency bins that have a lower amplitude than the current bin in order to count the current bin as a peak.

- HASH PEAK FAN OUT: 12 This is the number of peaks forward to look at when generating a hash.

- MINIMUM AMPLITUDE: 10 Peaks below this amplitude are eliminated, as they are unlikely to show up in clips.

- MAX HASHES PER LOOKUP: 128 Lookup episodes for this many hashes when building out match-histogram.

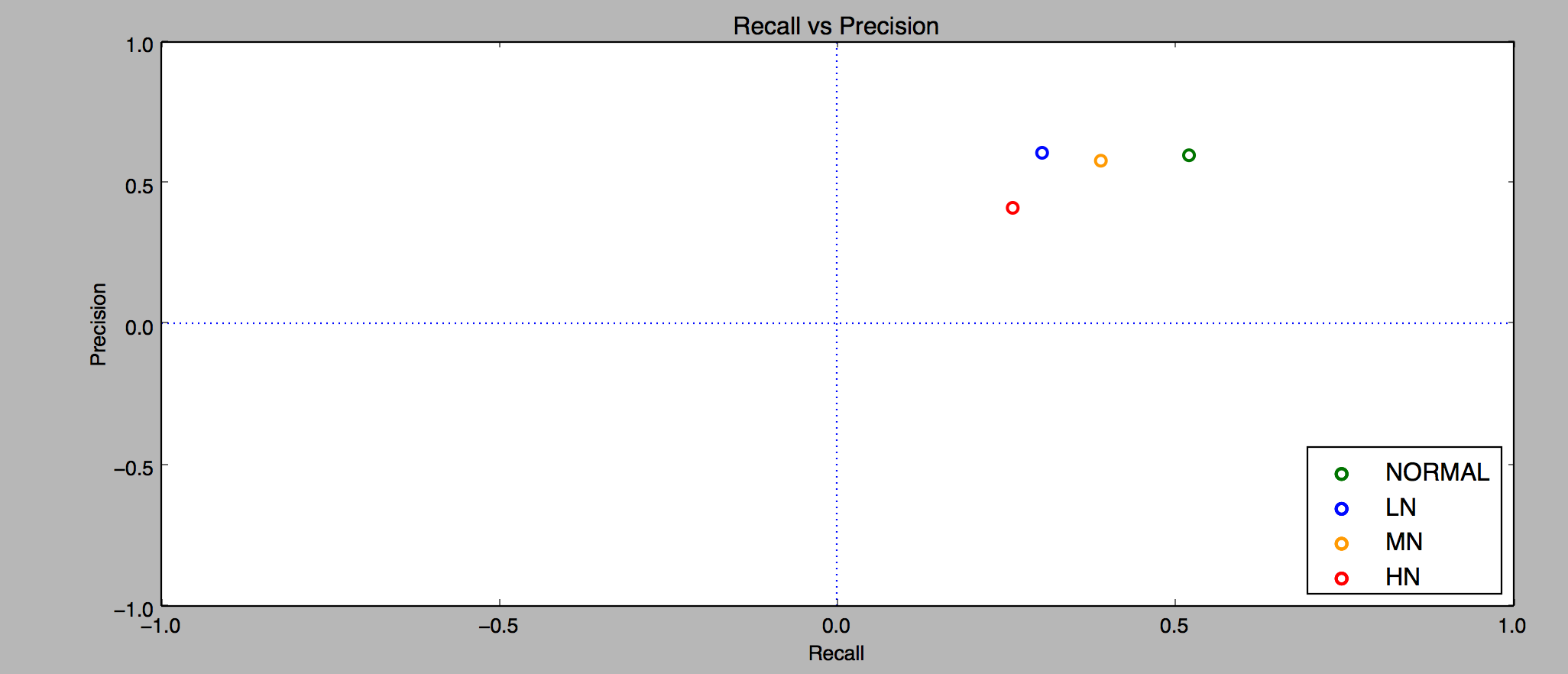

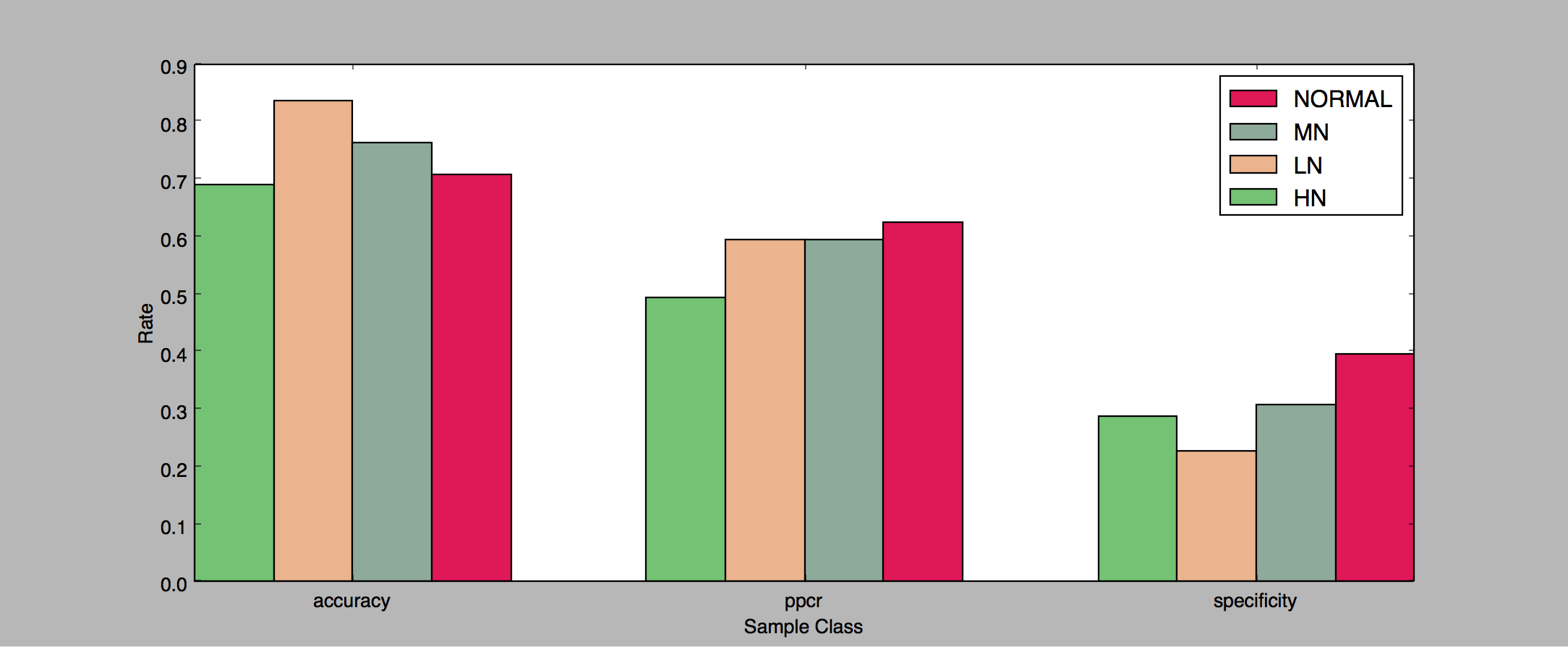

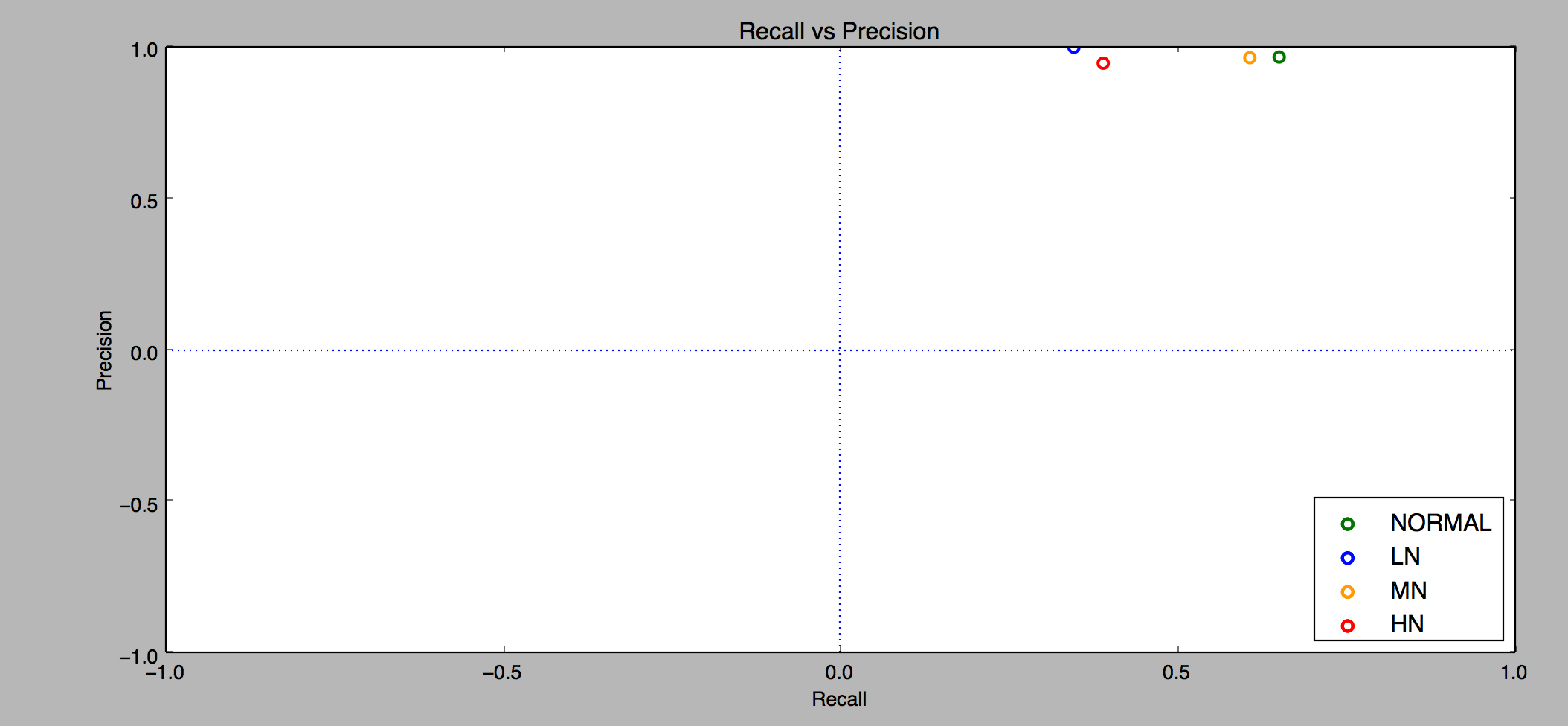

What the above image tells us is that the algorithm isn’t wrong more than it’s right. Which is not bad, but a long way from being good. Recall is calculated by tp / (tp + fn), and basically tells us what rate of identifications that were true identifications taking into account the ones we missed, and we want this to be 1. Precision on the other hand is tp / (tp + fp), or the rate of identifications that were true identifications. We also want this to be 1. By these measures, our algorithm needs a lot of work. Precision was 0.6 and recall was 0.52174 for the noiseless clips, so we were wrong a fair amount of the time.

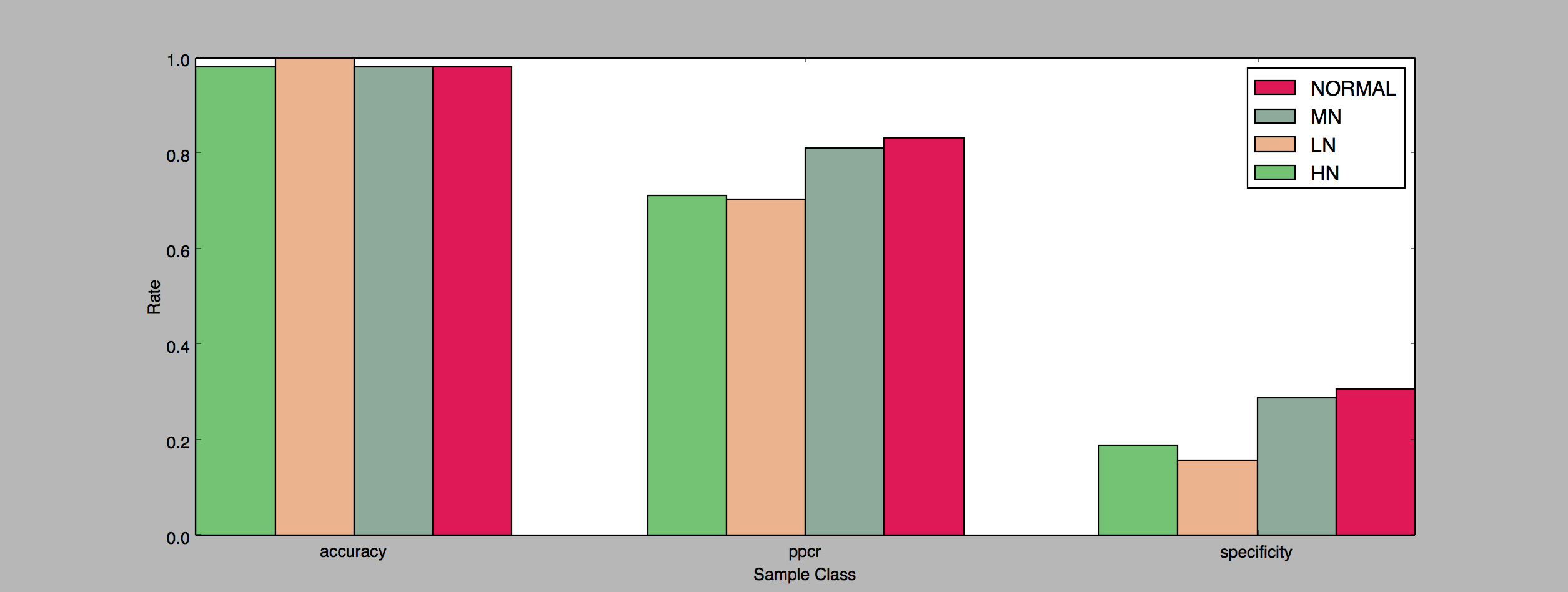

If we look at some more illustrative measurements, we see that we were still pretty off. Predictive positive condition rate (PPCR) tells us that our algorithm was confident enough to return a positive result 62% of the time. The Accuracy rate, which is by far the simplest measurement, just takes the number of times we were right about a clip out of the total number of clips. With the noise-less clips we were only accurate 70% of the time!

Run Number 2

Tuning the variables is obviously necessary. When we limit the number of frequencies we consider peaks, and lower the fan-out out of fingerprint algorithm we get fewer hashes. This, in combination with increasing the max number of hashes we match against our query to the fingerprint database, gives us much better numbers.

- PEAK NEIGHBOR COUNT: 20

- HASH PEAK FAN-OUT: 4

- MINIMUM AMPLITUDE: 20

- MAX HASHES PER LOOKUP: 512

On the one hand our precision rates were nearly perfect, and our recall rates were only slightly better. On the other hand, our accuracy rates for all noise classes were close to perfect!

Further Experiments

Something that I’d like to explore in the future is automating this process. If we have 4 variables that we can tune, each with 10 different values that we can guess would make a good fingerprint, we can automate the 10,000 combinations to load and test our algorithm to see which one gives us good results. Guessing what variable settings would make a good algorithm is an interesting process because it’s something I can intuitively do, but brute-forcing our way through it would ultimately yield better results.

So there’s a lot I didn’t do, and I think that’s a good note to end on. The database is far to large to be used in a real world scenario, but could be slimmed down depending on user experience (i.e. What’s the minimum number of hashes we need to make a match 99% of the time with a 5 seconds? What’s the minimum number to make it 99.999% of the time with 10 seconds?), and we could sample a larger number episodes from a TV show (How many episodes of Frasier are acoustically similar enough to fool us?). But this project shows not only that those questions are probably answerable, but that all that’s stopping us is time and data.